Jeanne Marie Beaumont - Impr ...

John Bradley - The Art of Sl ...

William Lusk Coppage - The C ...

Kyle Gray - Through the Fenc ...

Kathleen Hellen - On the Wes ...

Tyler King - Sustain

Lynne Knight - Dog Is Your C ...

Bonnie Wai-Lee Kwong - The R ...

George Looney - The Eternal ...

Sarah Maclay - 49

Marilyn Ringer - The Off-Han ...

George Wallace - bridget

|

|

|

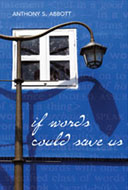

if words could save us

if words could save us